Immigration policy shapes the destiny of the nation.

—Anthony Kennedy, Arizona v. the U. S. (2012)

Self-sufficiency has been a basic principle of United States immigration law since this country’s earliest immigration statutes.

—USC Title 8, Ch. 14 §1601 (1996)

The Story of Ruth

There was famine in Israel. A man named Elimelech took his family out of Bethlehem in Judah into the pagan land of Moab on the other side of Jordan (Ruth 1). There he died. His two sons married nice Moabite girls, and then both brothers died as well. Only Elimelech’s wife Naomi was left—she, and her two daughters-in-law, Orpah and Ruth.

When Naomi heard that God had blessed His people and given them bread, she decided to return to Bethlehem. Orpah and Ruth wanted to go with her. Naomi objected. She could have no more sons, and if she could, these young women certainly wouldn’t wait for them to grow up. No, it would be better for them to remain in Moab with their own people.

Orpah listened to her mother-in-law and went home. Ruth didn’t. She clung to Naomi and refused to budge. She said:

Intreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God. (Ruth 1:16)

Naomi relented, and the two returned on foot to Bethlehem. It was the time of the barley harvest. When the townsfolk saw their old friend, they asked themselves, “Is this Naomi?” Time and sorrow had aged her considerably. She answered, “Don’t call me Naomi [Sweetness]; call me Mara [Bitter]: for the Almighty has dealt very bitterly with me” (1:20).

Quite a pair. An aged Israelite widow and young immigrant widow with no income and no marketable skills. In most places in the ancient world, their options would have been few and unpleasant. But this was Israel during a time of God’s blessing. Ruth knew exactly what to do. She went to glean in the fields outside the city.

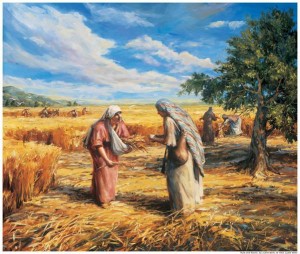

Ruth, an immigrant, works hard while gleaning a field.

Gleaning in Israel

We find the laws that govern gleaning in Leviticus and Deuteronomy (Lev. 19:9-10; 23:22; Deut. 24:19-22): Farmers were to leave forgotten sheaves in the fields. They weren’t to go over their olive trees or grape vines a second time at harvest. They weren’t to reap the corners of their fields or pick up every stalk that fell to the ground. All of this they were to leave for the poor— for the widow, the orphan, and resident aliens.

The Law prescribed no civil penalties for landowners who refused to allow gleaners onto their property. God required rural landowners to make their fields available, but the State couldn’t compel them. This was between the landowner and God. The landowner retained the right to reject any would-be gleaner who seemed disruptive, dangerous, or unsavory. “Gleaning was therefore a highly personal form of charity” (North, Leviticus, 203). Those who wished to glean had to maintain a public reputation for morality and responsibility. In a sense, they had to belong to the “deserving poor.”

Gleaning was hard, backbreaking work. The harvesters got most of the crops. The gleaners got enough to feed themselves and their families—maybe just a little more. The gleaner “had to invest more labor per unit of crop harvested than the piece-rate harvester did… To be a gleaner was to be in a nearly desperate condition” (Leviticus, 200). But from a biblical point of view, such exhausting work was better than a free handout. Created in the image of God, man was made for work and for dominion (Gen. 1:26-28). When he fails to work for his food, he fails in his humanity and in his piety. Though both Testaments provide other forms of charity for the truly disabled, both insist that those who want food and have the ability to work for it ought to do so. Paul writes: “For even when we were with you, this we commanded you, that if any would not work, neither should he eat” (2 Thes. 3:10).

Those gleaners who worked hardest or most skillfully might catch the attention of the landowner or his foreman. (Farmers always need competent workers.) An energetic gleaner might work his way into a (slightly) higher paying position at the next harvest, and that might be a stepping-stone to other opportunities. North gives us this summary: “Israel’s gleaning system made the charity local, work-oriented, and a source of profitable information regarding potential employees. Thus, the system offered (and offers) hope to those trapped in poverty” (Tools, 820).

The gleaning system, however, operated only in the countryside. There was no corresponding system for Israel’s cities. The net effect would have been to drive the most desperately poor out of the cities and into the fields. This reinforced Israel’s tribal arrangement of land, and the Promised Land, together with its tribal divisions, played a key role in the promise of Messiah. The Promised Land was Immanuel’s Land (Isa. 8:8). “Thus, the gleaning law was part of the social order associated with Old Covenant Israel. It reinforced the tribal system. It also reinforced rural life at the expense of urban life—one of the few Mosaic laws to do so” (North, Leviticus, 201).

God is no longer concerned with the location, distribution, and separation of the tribes of Israel. Immanuel has come. But there are still some abiding principles here:

- The poor, even the deserving poor, do not have a legal claim on anyone else’s property.

- God’s law doesn’t give the State the authority to redistribute wealth (steal from taxpayers) in order to alleviate poverty.

- Charity works best where the one who gives knows the character and needs of the one who receives.

- The best sort of welfare program is one that allows and requires the deserving poor to work for their food or money and rewards them according to their diligence.

- Farmers and urban businessmen would do well to see how they might make their unused resources available for modern forms of gleaning.

- Those who give to the poor should discriminate on the basis of moral character, not ethnicity or national origin.

Immigration in Israel

And so we come to immigration in Israel. Israel was to expect a great deal of it. God commanded Israel to treat her immigrants with justice and kindness (Ex. 23:9; Deut. 10:18-19). This meant equal justice under the law, certainly (Lev. 24:22; Num. 15:15-16). But Israel’s laws were God’s laws. The nations would hear of them and say, “Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people” (Deut. 4:6). God’s law-order would provide justice, liberty, and economic opportunity for all who came to sojourn in Israel. This would draw many to Israel. But even beyond this, the nations would hear of Yahweh and of His great works, and many would come to worship and serve Him with His people (2 Chron. 6:32-33). All of this was part of God’s plan that Israel should be a priest to the nations (Ex. 19:5-6). So God commanded this:

And if a stranger sojourn with thee in your land, ye shall not vex him. But the stranger that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God. (Lev. 19:33-34)

God’s law made no distinction between legal and illegal aliens. It did distinguish between resident aliens and citizens. In Israel, citizenship was tied to covenant membership. Circumcised males who faithfully attended the required feasts and who served in Israel’s militia were members of the congregation. In modern terms, they and their families were citizens. Immigrants could become citizens, though in some cases it took multiple generations (Deut. 23:3-8).

Immigrants could live anywhere in Israel they could rent or buy a home. They could lease tribal lands, but only until the Jubilee; they couldn’t buy them (Lev. 25). They could do business, earn wealth, and move about as they pleased. If they were poor through no fault of their own, they were entitled to the private charity of God’s people, beginning with the opportunity to glean. But Israel had no State welfare programs, either local or federal. She had no government-funded schools. She had no federal medical programs. What Israel had was liberty.

Immigration in America

America isn’t ancient Israel. We have State-financed health, education, and welfare programs in abundance. All of them have costs, not all of which are apparent. Open immigration would have financial and legal complications for the United States—and for the individual states—that weren’t an issue for ancient Israel. What exactly those complications might be and what we should do about them is a matter for research and debate. David Griswold’s essay, “Immigration and the Welfare State,” might be a good place to start the discussion with regard to projected costs.

Still, in the face of all complications, we must confess that God’s law exhorts a godly people to welcome law-abiding immigrants who want to work. Nowhere, however, does it require anyone but the immigrants themselves to bear the cost. The United States’ official immigration policy seems generally consistent with this vision. Congress has said that:

(1) Self-sufficiency has been a basic principle of United States immigration law since this country’s earliest immigration statutes.

(2) It continues to be the immigration policy of the United States that—

(A) aliens within the Nation’s borders not depend on public resources to meet their needs, but rather rely on their own capabilities and the resources of their families, their sponsors, and private organizations, and

(B) the availability of public benefits not constitute an incentive for immigration to the United States.

Whether or not the federal government and its agencies are currently observing this policy is, of course, another question.

Conclusion

Ruth’s story had a happy ending. She gleaned in the fields of Boaz, a wealthy landowner and near kinsman. Her godly character caught his attention, and within a few months he was ready to assume the role of kinsman-redeemer and marry her. Their great grandson was King David (Ruth 4:21-22): together, they became ancestors of Jesus Christ (Matt. 1). Israel’s immigration policy shaped not only its destiny, but that of the world as well. God’s law offers love and opportunity to foreign immigrants who are hard working and law abiding. Lawful immigration policies have played an incredible role in the spread and growth of God’s kingdom. Policies which reward the hard working and “deserving poor” must be rethought and reworked to further spread the good news of the gospel.

For Further Reading:

George Grant, In the Shadow of Plenty, The Biblical Blueprint of Welfare (Ft. Worth, TX: Dominion Press, 1986).

Gary North, Leviticus, An Economic Commentary (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1994).

Gary North, Tools of Dominion, The Case Laws of Exodus (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1990).

Daniel Griswold, “Immigration and the Welfare State,” Cato Journal, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Winter 2012).

1 Comment

One thing you failed tp point out in the story of Ruth. She came into Judeah with her mother-in-law, a Judean citizen, as her sponser. Ruth was not an alien who just walked across the border an setteled in .

Add Comment