And the people bowed and prayed to the neon god they made….

—Paul Simon

We were educated again and again that the emperor was a living god.

—Enomoto-san in Flyboys

The Making of a God

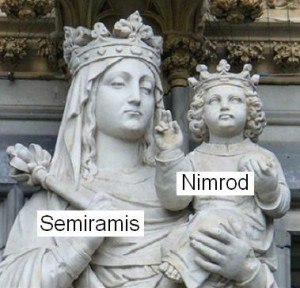

Semiramis becomes Queen of Heaven.

The year was 1854. Commodore Perry and his fleet had come and gone a second time, and Japan was in shock. His “Black Ships” had rocked the whole of Japanese culture. The Westerners obviously had a military technology that far surpassed Japan’s. This was both frightening and intolerable. Something had to be done. And so Japan’s military leaders began an in-depth study of the new threats from the West. They quickly saw that these emerging nations all had something in common: they were Christian. They had a single God whom they served and in whose name they carried out successful campaigns to extend their respective empires, or so it seemed. Japan had nothing of the sort, no single god who could unite the island or serve as an inspiration for the empire. And so the Japanese military-industrial complex of that time set out to create one.

They plucked the young emperor out of forced seclusion and made him a god, a Japanese god as an answer to the Western God called Christ. They called him Meiji, “Enlightened Rule,” and they draped his rule with the trappings of a constitution and Westernized laws.

All pure show to impress the Western nations.

The power of the puppet emperor was presented to their own people as absolute; only those who pulled his strings knew otherwise. Japanese schools taught this new variation of Shintoism with great vigor for the next century. When World War II came, the people of Japan were willing to live and die for their god-emperor, even if it meant turning the whole island into a bloody sacrifice. All of this James Bradley describes, almost in passing, as he sets the stage for Flyboys (2003), his account of the courage and perseverance of American pilots shot down during the Second World War.

Apotheosis

There is nothing surprising in Bradley’s summary. The human race has a long history of turning men into gods, and almost always for reasons of the power State. In the ancient world, the Pharaohs of Egypt reigned as sons of the divine Sun; Alexander was (apparently) pronounced the son of Amon (Zeus) by the Egyptian oracle at Siwa; and each of the Roman Caesars was declared divine upon his death. Sir James Frazer in his monumental classic, The Golden Bough (1927), devotes an entire chapter to chronicling the deification of mere mortals. His research stretches from Egypt to the South Seas, and from Africa to Burma. He knew his facts all too well. But when he came to explain how men could mistake other men for gods, he faltered. He suggested that, “Men mistook the order of their ideas for the order of nature,” and so imagined that the control they had over their own thoughts somehow implied a control over the external world as well. Frazer didn’t understand the human heart very well.

The Source of Mythology

Anthropologists and historians continue to argue over the source of Earth’s ancient mythologies. Some see in them an allegory of Nature, a symbolic representation of the Circle of Life. Some think they arise out of the inability of primitive man’s mind (or language) to deal with the abstract, with what we call “the laws of Nature.” Others see the ancient myths as a primitive human response to the celestial lights. Frazer saw them as an attempt to explain magical ritual when its real origins had been forgotten. Freudians see what Freudians see in everything, and followers of Jung and Campbell speak about archetypes that reside in the collective unconsciousness of humanity.

Mythology as History

One other approach to the origin of myth deserves a closer look. It bears the title “Euhemerism.” Euhemerus was a Greek scholar, a mythographer, who lived four centuries before Christ. He argued that the ancient myths were distortions or elaborations of historical events. He said that all the gods were simply deified men. He even pointed out their tombs. The writings of Euhemerus haven’t survived, though a number of ancient writers have passed on some of what he said. Cicero mentions Euhemerus in his own discussion of the nature of the gods (De Natura Deorum, I:xlii). And in his Tusculan Disputes, Cicero seems to share his opinions:

Nay, more; is not the whole of heaven…almost filled with the offspring of men? Should I attempt to search into antiquity, and produce from thence what the Greek writers have asserted, it would appear that even those who are called their principal Gods were taken from among men up into heaven. Examine the sepulchers of those which are shown in Greece; recollect, for you have been initiated, what lessons are taught in the mysteries…(I:xii, xiii).

The early Christian apologists agreed: the Greek and Roman gods were only deified men. Their opponents never denied it. Since there was a god-man on the throne of the Roman Empire, perhaps there wouldn’t have been much point.

The details of the myths varied from one nation to another, of course. This was only natural. As one nation acquired deities and mythologies from another, it would naturally reinvent them, and combine the new with the old and familiar beliefs. Names would change as would the details and finer points. Often the core belief system would even be lost. This is what happened with the ancient Greeks, who learned their gods and religion from Egypt, Phoenicia, and Babylon. The Romans, of course, picked up most of their mythology from the Greeks. But where did it all start?

Prototypes

Scripture associates the rebellion at Babel with an attack on God’s sovereignty. A piece of magical technology or the “Stairway to Heaven” Robert Plant told us about. Scripture also tells us that the mighty hunter Nimrod created the first postdiluvian empire beginning at Babel and that he carried his tyranny forward into Assyria. In fact, he founded Nineveh as his new capital of his “world” empire (Gen. 10:11, margin; cf. Mic, 5:6). Secular historians call the founder and first king of Nineveh, Ninus. His wife was the legendary Semiramis. Nimrod (Ninus) died suddenly at the height of his power; Semiramis took his throne and ruled successfully for another forty years. Her exploits, like her husband’s, were legendery.

That both this king and queen were deified upon their deaths seems clear enough from the ancient writers. But many later writers have also seen in these two the prototypes of the husband and wife deities that recur throughout the ancient mythologies: Osiris and Isis; Marduk and Ishtar; Baal and Astarte. These same writers assert that the process of deification began well before Semiramis’s own death, though it came in a rather clouded fashion, dressed in mystery.

The Dying God

The mystery religions tell of a young man, a son of the gods, who died a violent death. He may have hung on a tree. Throughout the ages, he has been called Adonis, Tammuz, Horus and Bacchus. In Northern lands, he was Balder the Beautiful. But whatever his name this young man, amidst the weeping and wailing of his worshippers, always came back to life, glorified and victorious. His goddess mother (or lover) rejoiced in his return, and all Nature celebrated with renewed life. The world was reborn.

Are these examples really an allegory or ritual about the circle of life? Or are these stories clever pieces of political propaganda from the priests and well-connected string-pullers of their day? Did Semiramis invent a story like this to exalt her royal child and enhance her own power? Whatever the historical and political origins of manufactured deities may be, we can be sure that the ancient priesthoods carefully concealed the truth about the new gods—perhaps an easy thing to do in the wake of Babel when written language and record keeping were still being reinvented.

The Purpose and Root of Mythology

So which is it? Does myth arise out of willfully distorted history, out of political hoax and manipulation? Or does it arise as an imaginative picture of the procreative cycle of Nature? Then again, maybe it’s simpler. Maybe fallen man invents fertility religions simply because he likes to visit temple prostitutes.

It’s indisputable that pagan culture worshipped Nature. In the sun and the storms, paganism perceived a male dimension of the natural order. In the fertile, verdant Earth, it saw a female dimension. The land died in autumn and returned to life in the spring. The sun and storms brought life to the Earth. Pagan culture personified this worldview. To tie those personifications to real people would have been an obvious step when that world-view was first taking root—a useful step for those in power.

Of course, none of this addresses the real root of idolatry. St. Paul tells us that idolatry begins in a thankless heart (Rom. 1:21-23). When Adam and Eve stood in Paradise and reached for forbidden fruit, they weren’t content. They weren’t thankful for the world and the roles God had given them. The truth is that some men do worship false gods so that they can visit prostitutes, some so that they can steal, and others so they play power politics. Gods can be handy things for those who are not content with their lot.

But why have gods at all? Because we are inescapably made in the image of God. We are inherently religious beings (Gen. 1:28). We are too small in too many ways to be alone in the universe. So when we forsake “the fountain of living waters,” we always hew out “cisterns, broken cisterns, that can hold no water” (Jer. 2:13). As John Calvin wrote, our hearts are idol factories. This is what Sir James Frazer never understood. This is what anthropologists still don’t understand. But the misunderstanding is willful.

A Footnote on Similarities

Unbelievers today point to the dying god myth as the origin of the Christian gospel. But a few formal similarities apart, the religion of the dying god could not be further removed from biblical Christianity. The pagan “dying god” paradigm attempts to save humanity from pain and death. The dying god passes in triumph beyond these things and he invites a spiritual elite to follow. What is required is a ceremony, a ritual, an experience, a series of actions that will lift man out of his present existence onto a higher plane. The dying god is the path maker and his followers also become gods in the making.

In other words, the pagan version of the dying god extricates humanity from bad situations and prepares them for the next level in the chain of being. He does not deal with sin itself or with guilt. In fact, the pagan world-view has no conception of sin, for sin presupposes a sovereign Lawgiver, a Creator—nothing less. But in pagan mythology, there was no Creator. The universe was self-existent, and the gods were its evolving offspring. The dying god deals in magical metaphysics and cosmic evolution. The Christian gospel deals in ethics and grace and covenant love. The gulf between these two views is larger than the Universe itself.

Add Comment