If there are no laws made in heaven, by what standards should human society organize itself? —Gary DeMar

In reality, theocracy in Biblical law is the closest thing to a radical libertarianism that can be had. —Rousas J. Rushdoony

Theocracy in the Ancient World

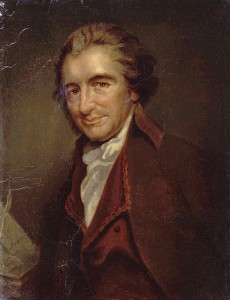

The word theocracy has a ring to modernists that sets it on par with holocaust, jihad, and storm trooper. The word actually means “the rule of God.” Older dictionaries say that it means the direct rule of God in human affairs or the rule of men in direct communication with God. Theocracy is not properly the rule of priests or clerics, unless these men are the recipients of immediate and ongoing divine revelation. Theocracy is God Himself reigning on earth. Thomas Paine’s impassioned call for early American theocracy couldn’t be any more clear, when in Common Sense he declared, “But where, say some, is the King of America? I’ll tell you, friend, he reigns above.”

In the ancient world, most nation-states thought of themselves as theocracies; that is, as nations ruled immediately by God. The god in question wasn’t the nation’s chief priest or oracle. Their god was their king, polis, or empire. God was Pharaoh, Alexander, or Caesar. God was the political power immanent in the State.

The remarkable exception to this was Israel, particularly in the days before the monarchy. Israel was a theocracy to be sure, but the divine Ruler was no human king, but God Himself. According to Scripture, God manifested His glory or presence in the Holy of Holies, the inmost chamber of the sacred Tabernacle.

But God’s presence was shrouded by veils and guarded by a sacrificing priesthood. After Moses’ death, rarely did any man hear the voice of God with his own ears. Occasionally, God spoke to Israel by His prophets. But for the most part, God committed the regular, daily functions of Israel’s civil government to magistrates who were to operate in terms of His revealed law. Israel’s was a government of written laws. Practically, this meant that theocratic Israel was a remarkably free nation, especially when compared to its neighbors.

"But where, say some, is the King of America? I'll tell you, friend, he reigns above."

The Old Testament Theocracy

Israel was a confederation of twelve tribes that were united religiously by their covenant with Yahweh, liturgically by their system of worship, and politically by their court system and laws. Her civil magistrates were chosen by the people; God didn’t prescribe the means of election. The magistrates were to be able, honest men who knew God’s law. Scripture does give us one example of a woman serving as a judge—and as high judge at that: Deborah the prophetess (Judg. 4—5). The magistrates were to enforce God’s civil laws and lead by moral example.

Israel’s judicial system consisted of graduated courts serving families of 10, 50, 100, and 1000 (Ex. 18:13-26). In our terms, this would be something like a judge for each neighborhood, for each larger collection of neighborhoods, for each quarter of a town, and for each town or small city. Judges could remand difficult cases to the superior courts. Probably appeals by the contending parties were possible as well. At the top of the judicial pyramid was a single judge who dealt only with the most difficult cases. Originally this was Moses; upon his death, Joshua; after that, the leaders named in the Book of Judges.

The high judge over all Israel usually served as the military commander for the nation as well. Samuel and Eli, who were priests, were apparently exceptions. So was Deborah, as women didn’t go to war. Only males who were twenty or older normally served in the militia (Num. 1:2-3); there was no standing army. Soldiers who were newly married, new home- or vineyard-owners, or just plain chicken were sent home (Deut. 20:5-9). The law made no provision for wars of aggression.

Israel had no standing legislature. Her basic laws were those given by God: the Ten Commandments and the case laws that explained and applied them (Ex. 21—23; Lev. 18—19; Deut. 12—25). Everyone was expected to know them. God’s law authorized Israel’s judges to punish crimes against human life and limb, marriage and sexual purity, private property, and public reputation. It also authorized action against public idolatry, false prophecy, and Sabbath breaking—all relatively public acts. The judges, however, had no authority to compel men to worship Yahweh or to renounce pagan beliefs. Israel’s civil laws did not meddle with the human heart or conscience. Furthermore, no case could be prosecuted without two or more witnesses to the same overt act or the equivalent in circumstantial evidence (Deut. 19:15; cf. Josh. 7:19-26). There was no allowance for eavesdropping, unwarranted searches, or torture.

Israel also had no prison system. Men accused of a crime could be confined briefly until their trial, but no longer (Lev. 24:12). God’s law authorized restitution, whipping, and execution as permissible sanctions. Those who could not make the required restitution could be placed in penal service until the debt was paid (Ex. 22:3). But a man working off such a debt would be attached to a godly family, not shut up with incorrigible criminals or in solitary confinement. Trials were public and speedy, and all sanctions were carried out quickly and in the open. Justice was a public matter and a concern to all.

The civil laws encouraged public charity, but for the most part did not compel it. The third year tithe, zero-interest loans, and gleaning were all part of Israel’s religious welfare system (Deut. 14:28ff; 23:19ff; 24:19ff). But God did insist that His civil laws be applied without discrimination or bias to rich and poor, citizen and immigrant, alike (Lev. 24:22). And God repeatedly reminded His people to show mercy and compassion to the widow, the fatherless, and the stranger (Deut. 14:29; 16:11; 24:17-22). In fact, He warned Israel that He would avenge the fatherless and widow Himself if His people or their magistrates failed in this civic duty (Ex. 22:22-24).

The New Age

The Tabernacle and its rites foreshadowed the coming Messiah (Heb. 8—10). In Jesus Christ, God became flesh and tabernacled among men (John 1:14). Jesus is Priest and Sacrifice, Tabernacle and Temple, Prophet and King. The earthly Tabernacle and Temple are gone. So is the earthly theocracy. Jesus is in heaven, and His kingdom is Spiritual and international. Because of this, it would be a mistake to thoughtlessly cut and paste every one of the Mosaic laws into our own law books. But at the same time, Israel’s laws were good and wise, and her civil practices were consistent both with God’s grace and with godly liberty. In fact, God said this of His laws:

Keep therefore and do them; for this is your wisdom and your understanding in the sight of the nations, which shall hear all these statutes, and say, Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people…And what nation is there so great, that hath statutes and judgments so righteous as all this law, which I set before you this day? (Deut. 4:6-8).

“Isn’t That In The Old Testament?”

But for most American Christians today, Israel’s civil laws had one fatal flaw. They were given in the Old Testament. American Christians generally believe that Old Testament law was primitive, brutal, and strange. What’s more, they are convinced that law as law is a form of spiritual bondage.

As a consequence of this theology, most American Christians don’t have a clear standard for structuring or reforming civil government. They really haven’t thought much about the issue. We have to have laws. But if not God’s laws, whose? Those who have thought through it usually appeal to some vague notion of natural law. Some have become disciples of John Locke. Some have become civil libertarians.

The Rise and Decline of Natural Law

But natural law is at root, a pagan invention. When Alexander’s conquests transformed the world into a Hellenistic empire, the Greek polis—the individual city-state—failed thinking men as a source of absolute law. Hellenistic philosophy found itself wrestling with meaning and law in an increasingly cosmopolitan world. In the end, the Stoics tried to root law in Nature, in the divine intelligence or logos inherent in the cosmos itself. Law would be accessible to all right-thinking human beings. Roman intellectuals followed suit. “For there is one universe made up of all things, and one God who pervades all things, and one substance, and one law, one common reason in all intelligent animals, and one truth… ” So wrote the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius, persecutor of Christians (Meditations, VII, 9).

Mediaeval theologians, philosophers, and legal experts smuggled natural law into Christian theology through the door marked “natural revelation.” That is, they confused Stoic natural law with “the work of the law” that remains in the heart of every man (Rom. 2:14-15) and totally ignored the natural depravity that resides there as well. The confusion held through the Reformation and into the Enlightenment: Greece to Aquinas to Locke. But while Christians today continue to babble incoherently about with natural law theory, most humanists have jettisoned it altogether. The excuse was Darwin.

Darwin’s doctrine of evolution completely rewrote man’s understanding of Nature. Nature was no longer a given. It was no longer a fixed metaphysical reality on which philosophers could hang their systems. Nature was process, change, becoming. Nature was Hegelian synthesis, bloody red in tooth and claw. Natural law for most thinking people died in Stalin’s purges and Hitler’s death camps. Think about it. If law is rooted in nature and nature is all, without a fall, then what is in nature, is right. (I’ve always asked my kids, “What is there about a mother hamster eating her young, that I can base a civil law code?”)

By What Standard?

Humanism has left us without moral and legal absolutes. Any modern search for ethics, whether personal or civil, is mere experimentation with alternate lifestyles. It’s smorgasbord law. What do we like today? And, because human depravity always declines and degrades over time, what we like today will certainly be worse than what we liked yesterday. Romans 1 describes this decline in grim and gritty detail.

But God’s law provides absolutes. The psalmist was able to sing, “I will speak of thy testimonies also before kings, and will not be ashamed. And I will delight myself in thy commandments, which I have loved” (Ps. 119:46-47). Paul wrote, “Wherefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy, and just, and good” (Rom. 7:12). Jesus and Paul both quoted from the Mosaic cases laws and gave them practical application (Mark 7:10; 10:19; 1 Cor. 9:9). Though Paul refused the law as a means of salvation, he nevertheless affirmed that the law is good “if a man use it lawfully” (1 Tim. 1:8). Grace seems to have a lawful use for law.

Conclusion: What It’s Really All About

Theocracy is to this generation what nuclear war was to the last: unthinkable. Yet Christianity has always professed that Jesus is Lord of all, that the universe is, in fact, a theocracy. The message of the New Testament is the gospel of the kingdom (Mark 1:14). But that gospel message is the good news of atonement and resurrection, the good news of new birth and forgiveness. But it’s also a message that men and women must receive by faith. And faith can never be forced—not by swords, guns, or even Joel Osteen CDs.

Evangelism, prayer, worship, charity, and faith. These are the weapons of the Church (2 Cor. 10:14). But because the Spirit of God is at work in and through these things, the kingdom continues to come. Men and women become Christians and hopefully Christians learn to keep Jesus’ commandments. Sometimes they even learn to vote their consciences. And this indeed frightens the humanistic left. Here’s why: The issue is not really theocracy at all; the issue is morality. Humanists hate God’s laws. The “natural law” of human nature is to want to sin with impunity. If history shows us anything, it shows us this. May God have mercy on us for forgetting His Word.

For Further Reading:- Gary DeMar, Ruler of the Nations, Biblical Principles for Government (Ft. Worth, TX: Dominion Press, 1987).

- Gary North, Healer of the Nations, Biblical Principles for International Relations (Ft. Worth, TX: Dominion Press, 1987).

- James Jordan, “Calvinism and ‘The Judicial Laws of Moses’” in The Journal of Christian Reconstruction, vol. 5, no. 2 (Winter 1978-79), 17—48.

- Greg L. Bahnsen, By This Standard, The Authority of God’s Law Today (Tyler, TX: The Institute for Christian Economics, 1985).

2 Comments

I do fear a Rick Santorum-esque right-wing fervor, as a kind of fascist takeover. The government cannot mandate a moral people. Besides, who is to monitor the morality of the government?

I certainly don’t, however, fear people expressing their faith in public. Nevertheless, the Herman Cain’s of the world would have you believe the muslims are about to install shariah law across America, while I am sure the vast majority of Islamic peoples would probably say the exact things this article says- that a “caliphate” doesn’t mean that Imams and mullahs be our political leaders. It is about one’s faith being the most influential factor for their moral behavior- rather than the threat of prosecution by the state.

I do not fear a Rick Santorum type fevor as facist at all, that is taking his views to an extreme. It is true that the government cannot mandate a moral people, but the people can mandate a moral government!

Add Comment