But at this seat of government there must be a fitting memorial to the God

who made us all. . . . It should be a center of prayer, open to all men of all faiths at all times.

—President Lyndon B. Johnson, Presidential Prayer Breakfast (1964)

Perhaps a Golden Calf would be appropriate?

—Jacos R. Brackman, The Harvard Crimson (1964)

An Offer of Help

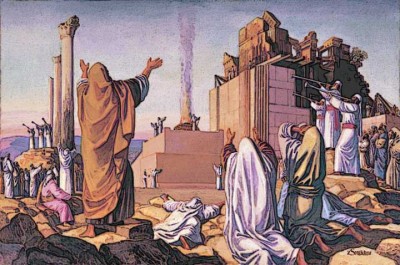

When Israel dedicated the foundation slab for the new Temple, the assembled people made such a great tumult of mingled joy and sorrow that folks from a long way away heard the sound and talked about it to their neighbors. Eventually word of this completed first phase reached the political leaders of the Samaritan communities. They came to investigate and offer their support.

When Israel dedicated the foundation slab for the new Temple, the assembled people made such a great tumult of mingled joy and sorrow that folks from a long way away heard the sound and talked about it to their neighbors. Eventually word of this completed first phase reached the political leaders of the Samaritan communities. They came to investigate and offer their support.

“Let us build with you. For we seek your God as you do” (Ezra 4:2). Samaria’s leaders assured the elders of Israel that they had served God and sacrificed to Him since the Assyrians had first moved their various peoples into Palestine more than a century and a half before. Since they worshipped the same God, it only made sense that their mingled peoples should work with Israel to rebuild the temple.

But Zerubbabel, the prince of Judah, and Jeshua, the high priest, saw things differently. Together with the other elders, they said, “You have nothing to do with us in building a house to our God; but we alone will build to the LORD, the God of Israel, as King Cyrus the king of Persia has commanded us” (v. 3, ESV).

What It Was Really All About

At first blush, the response of Israel’s leaders might seem harsh and arrogant, even bigoted. Here are seemingly sincere people asking to participate in a religious project dedicated to their common God. They only ask to help. And it’s not as if the elders of Israel had rejected all Gentile help. As they themselves admitted, they were operating under a grant and charter from the Persian emperor, Cyrus. They also paid men of Tyre and Zidon, Canaanites, to provide them with cedar wood from Lebanon.

To understand the elders’ reaction, we need to see what went before and what follows in the text. When the peoples who would become the Samaritans were first transplanted into Palestine, they brought with them a wide variety of idols and religious practices (2 Kings 17:24ff). Because they did not acknowledge God’s sovereignty over the land, He sent lions among them, creating a lot of carnage.

So the Samaritans appealed to the king of Assyria: “We don’t know the manner of the God of this land!” The king dispatched an Israelite priest, apparently a priest to the golden calf at Bethel, to instruct these peoples in the worship of Yahweh. What developed out of this was the Samaritan religion, a synthetic and developing religion that used the name of Yahweh but ignored His Word.

The Bible records the ongoing idolatries of the Samaritan people and then says this:

So they feared the LORD, and made unto themselves of the lowest of them priests of the high places, which sacrificed for them in the houses of the high places. They feared the LORD, and served their own gods, after the manner of the nations whom they carried away from thence. Unto this day they do after the former manners: they fear not the LORD, neither do they after their statutes, or after their ordinances, or after the law and commandment which the LORD commanded the children of Jacob, whom he named Israel (vv. 32-34).

Notice the cadence and the sarcasm: “They feared the LORD . . . They feared the LORD . . . they fear not the LORD!” In other words, the Samaritans didn’t worship the God of Israel. Rather, they practiced a syncretistic religion of their own making.

The basic enmity between the two religions becomes even clearer in the events that followed the dedication of the foundation. As soon as the Samaritan leaders had been rebuffed, they set about frustrating the work at Jerusalem (Ezra 4—5). They worked at the local level and at the Persian capital. They “hired counselors against them to frustrate their purpose, all the days of Cyrus king of Persia, even until the reign of Darius king of Persia” (4:5). They wrote letters accusing the Jews of having revolutionary and treasonable intentions. The letters appealed to Jerusalem’s “colorful” history and piled up epithets—rebellious and hurtful—to strengthen the Samaritan’s case.

The Samaritans got what they wanted, at least for a time. The emperor forbade any more work on the city, and the Jewish people stopped work on the Temple as well. And there matters rested until God sent the prophets Zechariah and Haggai.

The Roots of “Building Together” in America

The modern ecumenical movement came of age in the early 20th century, but its beginnings lie in the previous century, particularly in American Transcendentalism and in the religious, artistic, and social movements it influenced. Transcendentalism took America away from the creeds and confessions, away from Scripture and reason, to a pantheistic universe in which all faiths and creeds, insofar as they meant anything at all, led to the ultimate unity of all things.

The Transcendental authors still spoke freely of God and Christ, but most Americans didn’t understand that these words had been stripped of their biblical and creedal content. For example, when Emerson expressed his pantheistic faith in his short poem, “Brahma,” he found that many of his readers were confused. He told his daughter, “If you tell them to say Jehovah instead of Brahma, they will not feel any perplexity.” Names no longer matter when all is one.

Transcendentalism gave Unitarianism a new lease on life and turned it lose on evangelical Christianity, especially Calvinism. A shift away from the doctrines of sovereign grace and toward Arminian theology took place throughout the American church. “There can be no doubt that transcendentalism had a permanent influence on nearly all of the established denominations; it also gave rise to new cults, which reflected even greater departures from the historic Christian faith” (Singer, 13).

The Transcendentalists and their disciples, discarding the doctrine of total depravity, took up the cause of reform. The defeat and reconstruction of the South were the first goals, but with those accomplished, the would-be evangelists looked to for bigger fish to fry: the pursuit of utopia, a secularized Millennium. They looked to the Church of the Future, a single religious body that would incarnate the new Religion of Man. And to this future they turned their time, energy, and resources… towards Darwin.

It shouldn’t be a surprise, then, that the evangelical desire for greater cooperation quickly took a hard left turn toward modernism, the social gospel, neo-orthodoxy, and finally syncretism—the union of all religious faiths. The plea today is, “It’s the same God we all worship,” but that god is the idolization of man-centered creeds and ethics. The Christian creeds are dead, and even Scripture must not be read as if it contained absolute, propositional truth. We no longer want words. We want love; we want feeling, we want experience.

One Way, One Truth, One Life

Listen up: We do not all worship the same God. The God of Scripture is the Creator of the universe. He is ontologically distinct from the world He made. He is, therefore, its sovereign Ruler, Lawgiver, and Judge. Our basic problem is not ontological (a deficit or estrangement of being) but ethical. Man is in rebellion against God and deserves eternal hell. (That’s what the Bible says in no uncertain terms.) If man is to be saved from the wrath to come, God must save him.

The Gospel tells us that God offers salvation to men through the finished work of His only begotten Son, Jesus Christ. The Belgic Confession (1561) summarizes the Gospel message with these words:

We believe that God, who is perfectly merciful and just, sent his Son to assume that nature, in which the disobedience was committed, to make satisfaction in the same, and to bear the punishment of sin by his most bitter passion and death. God therefore manifested his justice against his Son, when he laid our iniquities upon him; and poured forth his mercy and goodness on us, who were guilty and worthy of damnation, out of mere and perfect love, giving his Son unto death for us, and raising him for our justification, that through him we might obtain immortality and life eternal.

This gift of eternal life must be received by faith and faith alone. That faith is not a feeling or an experience, though it may produce both. Rather, it is trust in Christ Himself, the Christ described propositionally in the words of holy Scripture. Those who will not submit themselves to the words of Scripture are strangers to the Christ of Scripture and to the God who made the universe. They have nothing to offer God and His Church except the very religion of rebellion that made Christ’s death necessary.

Shall We Build Together?

The Christian and, say, the Muslim or Hindu may cooperate in stopping crime, cleaning up a neighborhood lot or in giving CPR to a dying man. I have this in Belize. Many of my neighbors are Muslims and splendid people to boot. We can and should work together in peripheral things here on the island. So, we should cooperate, but in this case neither surrenders his theology or religious commitments in the process.

However, if someone asked me to “build a better Belize” with my Muslim friends… our authority, our standards, our visions for the future would be so different as to make this “building” an impossibility. This would be especially problematic if we were asked to bind ourselves together to this end.

The Christian is committed to the personal God who reveals Himself in Scripture. He is under His authority and bound by His word, both in his actions and his beliefs. He acknowledges one Savior and one solution for sin. And in worship, he comes to God through Christ alone, the Christ of the Gospels and the creeds.

And so, in matters of worship and faith, the Christian cannot and should not build together with unbelievers. Like Zerubbabel and Jeshua, we must say, “You have nothing to do with us.” Or as Peter said to Simon the sorcerer, “You have neither part nor lot in this matter: for your heart is not right in the sight of God” (Acts 8:21).

To the world, this will seem unloving and judgmental. Certainly it involves passing a judgment, or more accurately, agreeing with God’s judgment. But it isn’t unloving to tell a “walking corpse” that it’s dead and is in need of spiritual life, especially when we represent the God of resurrection and the God of life.

For Further Reading:

C. Gregg Singer, The Unholy Alliance (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House Publishers, 1975).

Rousas John Rushdoony, “The Religion of Humanity” in The Nature of the American System (Nutley, NJ: The Craig Press, 1965).

J. Marcellus Kik, Ecumenicism and the Evangelical (Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1958).

Gary North, Crossed Fingers, How the Liberals Captured the Presbyterian Church (Tyler, TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1996).