. . . Let your wisdom and godliness appear, not only in choosing such persons as will entirely love and promote the common good, but also in yielding them all due honour and obedience in their lawful administrations…

—John Robinson in Bradford’s History (1651)

In times of cultural failure and upheaval, there are usually two kinds of extremists. Those who abandon any established order as a thing beyond redemption, and those who remain within the system, hoping they can reform it. New England was settled by both sorts in turn — by Separatists and by Puritans. Let’s talk about the Separatists first, those intrepid settlers we Americans call the Pilgrims. Next time we will look at the Puritans.

The Separatists were English Calvinists who had separated themselves from the Anglican Church and eventually from England itself as they sought a place where they could worship God according to His word. At first they met privately, even secretly in homes. But when Church and State combined to “harry them out of the land,” they fled to the Netherlands. What they found there, however, was hard labor and a local culture with plenty of temptations and distractions. When they’d finally had enough, they fled. William Bradford chronicled the motives for the move:

Lastly, and which was not least, a great hope and inward zeal they had of laying some good foundation, or at least to make some way thereunto, for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but even as stepping-stones unto others for the performing of so great a work.

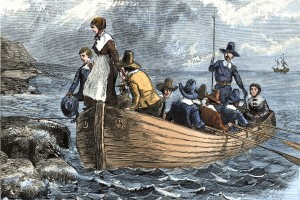

And so, through many difficulties and complications, they set sail for North America. When they neared this continent’s Eastern shores, a tempest blew their lone ship, the Mayflower, off course and set them outside the lands designated by their charter. And, in the face of potential mutiny from the “strangers” aboard, the Pilgrims drew up a compact as a foundation for political self-government.

And so, through many difficulties and complications, they set sail for North America. When they neared this continent’s Eastern shores, a tempest blew their lone ship, the Mayflower, off course and set them outside the lands designated by their charter. And, in the face of potential mutiny from the “strangers” aboard, the Pilgrims drew up a compact as a foundation for political self-government.

This Mayflower Compact was done “in the name of God” and with loyal acknowledgement of the political sovereignty of their king, James I. The Compact listed the Separatists’ broad goals as the glory of God, the advancement of the Christian faith, and the honor of king and country. Specifically, the Compact combined the signers and their families into “a civil Body Politick” so that they could, in the future, “enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the General good of the Colony.” Those who signed were most of the adult males aboard the Mayflower, as well as two apprentices.

The Pilgrims vs. Democracy

Clearly, the Pilgrims were strangers both to our modern brand of individualism and what we usually think of as the democratic spirit. First, they acknowledged themselves the “loyal subjects” of King James. They also bound themselves in terms of divine principles and under the authority of God Himself … and the Christian God specifically. They also foresaw the need for new laws and civil offices in the future, and they committed themselves to ordering this civil government in terms of English and biblical law.

The signers expected that they would, in due time, have proper elected or appointed officers who would make and enforce civil law. There was no commitment in the Mayflower Compact to any type of ongoing direct democracy. There would be governors and officers and it would be the duty of every man to humbly submit to their rule.

Foreseeing this, their first pastor, John Robinson, had admonished them with these words before they left for the New World:

Lastly, whereas you are to become a body politic, administering among yourselves civil government, and furnished with persons of no special eminence above the rest, from whom you will elect some to the office of government, let your wisdom and godliness appear, not only in choosing such persons as will entirely love and promote the common good, but also in yielding them all due honour and obedience in their lawful administrations; not beholding in them the ordinariness of their persons, but God’s ordinance for your good. . . And this duty you can the more willingly perform, because you are at present to have only those for you governors as you yourselves choose.

The Pilgrims and Liberty

Modern opinion treats the Pilgrims as champions of religious liberty and freedom of conscience. But this is not how the Pilgrims themselves would have spoken of their mission and goals. The Pilgrims covenanted together, first as a church congregation and later as civil body, to promote the Christian faith as they understood it. Their common faith defined and dictated the nature of their ecclesiastical and political community. To put it bluntly, those who wished to worship God on terms foreign to the Separatists’ theology … should go elsewhere. The original Separatists had no desire to compel others to worship biblically because they believed that coerced worship was no worship at all.

They refer to the impossibility of forcing the conscience incidentally, not for the purpose of advocating freedom of opinion. Sometimes the people who are in error are sternly dismissed, in the spirit of the old prophet — “Ephraim is joined to his idols, let him alone.” Sometimes they are alluded to with pitifulness; but for the most part the impossibility of forcing the conscience is brought in to condemn the action of those clergy who are striving to get a legal sanction for their scheme of Church Reformation, in order that it may be imposed on the whole nation. (MacKennal, 24).

The Pilgrims, being Congregationalist Calvinists, were unimpressed with the imaginations of men. Like Luther, their minds were captive to the Word of God. They believed in absolute truth, revealed infallibly and authoritatively in Holy Scripture. They took it for granted that a truly Christian people would want to obey God in all of life, including politics. They assumed that a Christian people, given the opportunity, would construct a Christian commonwealth, but they didn’t believe that any laws, even God’s Mosaic Law, could regenerate men and make them disciples of Christ.

Conclusion

The Separatists practiced congregational government within their churches. The “heads of households” … usually an adult male … called or elected the pastor and the elders. These elected officers led the congregation by teaching, admonition, and by example. In some matters however, the whole congregation voted. This form of church government laid a strong foundation for the way the Pilgrims’ would enact their civil government, as well. The strong traditions of English civil government also would play a large role in how they would stay in covenant with each other. Throughout both influences ran the Christian understanding of law, grace, and representation.

The Pilgrims, like their Puritan cousins, thought in terms of covenant. They believed in biblical absolutes and in the need for humble submission to God’s ordinances. What they didn’t accept was Greek or classical democracy and the modern idea that every man’s opinion is as good as ever other man’s. They were strangers to individualism and knew no law higher than God’s.

For Further Reading:

Alexander MacKennal, The Story of the English Separatists (London: Congregational Union of England and Wales, 1893).

Terrill Irwin Elniff, The Guise of Every Graceless Heart: Human Autonomy in Puritan Thought and Experience (Vallecito, CA: Ross House Books, 1981).

Rousas J. Rushdoony, This Independent Republic, Studies in the Nature and Meaning of American History (Nutley, NJ: The Craig Press, 1964).

Clarence B. Carson, The Rebirth of Liberty, The Founding of the American Republic 1760-1800 (Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., 1976).

Add Comment