He chose the eve of All Saints’ Day…because this was one of the most frequented feasts, and attracted professors, students, and people from all directions to the church, which was filled with relics.

—Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (1858-90)

The Day of the Dead?

From China to Mexico, the ancient world was haunted by the memory of unspeakable death. In some traditions it was the death of a god, and in others, the death of the world. For Scripture, it was a global Flood. This haunting found expression in rituals and myths that in some cases survived well into Europe’s Middle Ages. Some linger on today. The days set apart to commemorate this tragedy were sometimes celebrated in late spring, but more often in mid fall—usually at the beginning of November when the Pleiades reached their culmination. Some say the Celtic Samhain may have been such a day. The date is right: November 1st. But many neo-pagans to the contrary, there isn’t any evidence that the Celts celebrated Samhain with elaborate rites or rituals or that they considered it a bridge to the Other World. What’s more, Samhain was primarily an Irish affair and wasn’t recognized in Europe at large, and it was on the Continent that November 1st first became a Church holy day.

It may be a complete coincidence, then, that the mediaeval Church set apart two days at the beginning of November to remember the Christian dead. It named November 1st “All Saints’ Day” or “All Hallows” and November 2nd “All Souls’ Day.” And it’s likely that the customs that swirl around All Hallows’ Eve—Hallowe’en, as we call it—have more direct roots in Christian superstition and folk practices than in pagan idolatry.

Saints and Other Christians

Saints and Other Christians

To understand why the Church set up two different days to honor the Christian dead, we need to understand something of mediaeval theology, much of which continues in Roman Catholic theology today. For the mediaeval Church, saints were godly men and women who had done all that God required of them and more. That “more,” those extra good works, were called “works of supererogation.” More about that later. The saints, upon their deaths, went directly to heaven, where they beheld the face of God and could intercede for believers on earth.

The Church believed that God identified His saints through miracles that He wrought through them or for them. Sometimes the miracles came after a saint’s death in connection with his relics, his physical remains or his special belongings. Once the Church was able to verify the miracles, it would grant the saint formal recognition and add his or her name to its official list (canon). Of course, there would be a great many saints the Church would know nothing about. Many canonized saints had their own feast days. All Saints’ Day celebrated those and all the rest.

Purgatory: The Fires That Cleanse

But for the mediaeval Church, most Christians weren’t saints. In other words, most Christians weren’t ready for heaven when they died. Rather, believers usually died with some sort of venial sin still tainting their souls. Such sins required cleansing and some measure of temporal punishment. For though God could forgive sin, He couldn’t remit the earthly punishment due those sins or admit anyone still unholy into His presence. For these reasons, Purgatory was a theological necessity. It also proved to be a very nice cash cow for the church.

Purgatory was thought to be a place of penitential suffering. That is, a place where those in a state of grace could suffer the temporal punishments that God’s justice required. When those punishments were done, the soul would be free to pass on to heaven. The length of punishment and degree of suffering would naturally vary from soul to soul, but in time every soul would ascend to God’s presence and behold His face. For Purgatory was only for Christian souls. The souls there constituted the Church Suffering or the Church Penitent, as opposed to the Church Militant on Earth and the Church Triumphant in Heaven. All Soul’s Day was dedicated to the Church Suffering.

Indulgences: Get Out of Purgatory for a Price

Now we return to the saints and their extra good works. The Church taught that it had at its disposal a spiritual treasury consisting of the merits of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. Since the Pope held the keys of the kingdom of God, he was free, at his discretion, to apply these merits to penitent sinners. That is, the Pope could release a repentant soul from the normal earthly punishments his sins would otherwise have required. Eventually and logically, this papal power was extended to those suffering in Purgatory as well. The official pronouncement of such release was called an indulgence. Originally, an indulgence could only be granted to one who was sorry for his sins. But it the early 1500s, those who sold indulgences sometimes overlooked this requirement, at least where the dead were concerned.

“As Soon as the Coin in the Coffer Rings…”

On March 15, 1517, Pope Leo X offered an indulgence to anyone who would contribute money towards the completion of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Because of Leo’s shrewd financial arrangements with the more powerful monarchs and the Fuggers banking firm, much of that money never reached Rome. It acted as a bribe to keep the power elite of the time satisfied. And of course Leo had other projects at hand than just St. Peter’s. But none of this was public knowledge. The common people were told that they were contributing to the building of St. Peter’s and that their reward would be heaven itself.

Leo commissioned a Dominican monk, Johann Tetzel (1465-1519), to sell indulgences in northern Germany. Tetzel was a master showman and would have been a great televangelist today. He made remarkable use of songs, flags, and bells to advertise his product. He offered indulgences for both the living and the dead. One could buy assurance of heaven for one’s self. One could buy deliverance from Purgatory for one’s departed kin. Though Tetzel observed the requirement for repentance when he sold indulgences for the living, he was far more liberal when he sold indulgences for the dead. He claimed that the mere purchase of an indulgence would instantly free a soul from Purgatory; as Tetzel put it, “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from Purgatory springs.”

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was an Augustinian monk who lived in Wittenberg, Germany. He was a pastor, as well as a professor. Luther had long struggled with his own guilt-ridden conscience and finally found in Scripture a doctrine of grace and forgiveness that brought him peace and assurance of heaven. But there was a problem: the doctrine wasn’t that of the mediaeval Church or its scholastic theologians. It involved justification through imputed righteousness, the righteousness of Christ. And in 1517 Luther was still working to understand it himself.

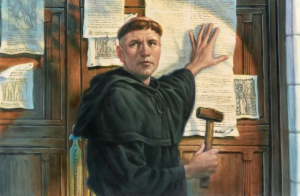

But when some of Luther’s own flock brought home newly purchased indulgences, he lost it. He denounced the efficacy of the papal promises. Tetzel responded by denouncing Luther. Then Luther took the theological battle to the next level. He wrote up ninety-five propositions (theses) for debate, all aimed at the abuse of indulgences. Being a scholar, he wrote in Latin.

The Ninety-Five Theses

When Luther wrote his Ninety-Five Theses, he still believed in Purgatory, the integrity and authority of the Pope, and the validity of indulgences. But the new trajectory of his heart and mind toward sovereign grace and justification by faith were already evident. For example, he wrote:

1. When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said “Repent,” He called for the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

36. Any Christian whatsoever, who is truly repentant, enjoys plenary remission from penalty and guilt, and this is given him without letters of indulgence.

37. Any true Christian whatsoever, living or dead, participates in all the benefits of Christ and the Church; and this participation is granted to him by God without letters of indulgence.

62. The true treasure of the church is the Holy gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

94. Christians should be exhorted to be zealous to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells.

95. And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

All Hallows’ Eve

Luther tacked his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the church on October 31, 1517. The next day was All Saints’ Day, and crowds would throng into the church to see its hoard of relics—some 19,000 of them. Luther thought that some theologian or scholar would pick up his challenge and rise to the debate. The response he got instead “went viral” beyond his wildest dreams.

Scholars across Germany translated, reprinted, and circulated Luther’s Theses. Within weeks, the flow of money to St. Peter’s had slowed to a trickle. Without any clear understanding of what was about to unfold, the papacy tried to get Luther to stand down. But one issue led to another. The issue of indulgences led to questions about the very nature of salvation. Questions about salvation led to questions of authority and epistemology. How do we know what God has said? Where does infallibility lie? Who or what is our final authority? Sola gratia (grace alone) and sola fides (faith alone) inevitably led to sola Scriptura (Scripture alone). The man of faith with his Bible in hand could stand against popes and emperors and declare, “Thus saith the Lord!” The fabric of mediaeval society began to unravel.

Conclusion

The Flood came in early November as the Pleiades reached their culmination. The world died in a day. But in the end, the Spirit of God renewed the life of the world and sent history marching on toward the coming Messiah. In the Reformation, the Spirit of God renewed the life of the Church and sent history marching forward in terms of a gospel of free and sovereign grace. If Hallowe’en is somehow a connecting link between these two historical events, we must confess that God indeed has a sense of humor.

Meanwhile, for many Reformed and Lutheran churches, October 31st is Reformation Day. It is a time to celebrate the mighty moving of God’s Spirit in history, a time to emphasize afresh the doctrines of justification by faith and the priesthood of all believers, and a time to remember those particular saints whom God used to change the course of Western history. As I write this from Wittenberg (visiting here with my father), my prayer is that we all remember that His Spirit can, once again, sweep the world with these powerful and efficacious truths.

For Further Reading:

Will Durant, The Reformation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957).

Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume VII (1910). Available online at <http://www.ccel.org/s/schaff/history/About.htm#_edn1>.

N. R. Needham, 2000 Years of Christ’s Power, Part Three: Renaissance and Reformation (London: Grace Publications Trust, 2004).